Microfinancing and Women

“Another world is not only possible,

she is on her way. On a quiet day,

I can hear her breathing.”

– Arundhati Roy

From past few weeks, I have been trying to garner an understanding of the scope and capacity which technology (ICT per se) holds when it comes to driving the science behind microfinancing. The idea is to first get a 30,000 feet view of the various dynamics of microfinancing and then to try and figure out the possible avenues where ICT can SERVE as a propellant.

In the course of the minuscule amount of reading that I have done, I have come across a very visible observation that is too difficult to miss. When you discreetly look at the participation trends of different groups in microfinancing, it is clearly visible that it shares a conjunctive relationship with women. All the inroads which microfinancing has made as an economic-micromanagement measure, a big overlap can be seen with the way women borrow and manage money. Women have been the biggest beneficiaries and at the same time the biggest impetus in the whole framework.

This outcome for some reason piqued my curiosity into looking up at the subject of women and microfinancing and I have tried to understand it first by revisiting a personal instance at home, second, by digging into the game-play between gender and poverty and third, by looking into institutions and organisations which fundamentally are the fore-bearers of this cycle.

Dadi’s insight, Santosh Bai

Santosh Bai has been helping us in our domestic chores even before my parents got married. She has deeply assimilated into our family. She works at 3-4 more houses apart from ours. Since the time she has been working, my Dadi has made a thumb rule for her monthly salary. She convinced Santosh Bai that she wouldn’t be getting her monthly salary for her work at our house, rather that amount will be put into bank only to be withdrawn at the end of the year. For her monthly expenses, she’d have to manage from the salary that she fetched from the remaining houses. You would say that Dadi acted in a Draconian manner here and hoarded the legitimate money that Santosh Bai deserved only to be granted to her at the end of the year. But wait, so my Dadi got a chance to study only up to the fifth standard. After that, she transitioned into a child bride. Some 80 odd years old at the moment, she carries an amazing mathematical ability and an eye for detail. The experience she garnered managing our 20+ people joint family at that time turned her into quite a good financial advisor as well. She identified that Santosh Bai, belonging to a lower middle-class family wasn’t able to save a lot out of all she made in a month. Just lecturing Santosh bai over the importance of saving wouldn’t have yielded anything and hence my Dadi took the matter in her own hands to ensure that Santosh Bai had some savings with her at the end of the year. These savings would obviously be laden with a decent increment from the interest that would be added. Santosh Bai over the years used these stipulated savings for relatively bigger investments like getting her children married and buying and building a house of her own. All this, she was able to do without borrowing a lot from other sources and this whole micro-savings system choreographed by my Dadi ensured that Santosh Bai held onto some kind of financial independence and decision making.

Not that this example carries any vehement crisscrossing with the fundamentals of micro financing. I still use it to put out a simple case of how very small level planning as an agreement between my Dadi and Santosh Bai made her financially robust when time required her to spend more than what her pockets allowed her. I will elaborate on how the women factor explicitly comes into the picture later in this same piece.

Poverty is sexist

A simple and categorical translation of the phrase above would go something like this – poverty affects women/girls more than men/boys. It can be also interpreted as a decrease in the availability of the biggest determinants of health, nutrition, education, economic opportunities and participation in decision-making to women as one goes down the GDP per capita ladder. We talk about the widening gap between rich and poor across the world. A more intricate focus on the issue tells us that within this divide there is a gender divide which exists when it comes to economic sustainability. As stated in the one.org report, If poverty has its way, and is left alone without outside influence, it will dictate the path for a child even before they are born. This path diverges for boys and girls and it is more difficult for girls, particularly in developing countries. The cycle goes like this – when it comes to primary education, girls are almost as likely to go to school as their brothers, but in case of secondary education the gender gap widens significantly. This widening of the gender gap thus results in a higher chance for a girl to be married young. Young brides form young mothers and it results in serious health and nutrition issues both for the mother and the child. Sexual violence, high risk of HIV (in Africa in 2014, 74% of new HIV infections in adolescents, for people aged 15-19, were among girls), death during childbirth are frequent byproducts of this cycle.

But all is not as despairful as it seems. There is a sequence I learned during my recent internship with a think tank—SENSE→THINK→ACT. The construct of the ‘feminisation of poverty’ has helped to give gender an increasingly prominent place within international discourses on poverty and poverty reduction which takes into account the sense part if the sequence.

As in the case of the latter two stages of the sequence, I will delve into microfinancing and how it helped in atleast a partial economic emancipation of women if not full.

SEWA, Grameen Bank – targeted interventions

In 2014, 90% of women in high-income countries had access to a financial institution, compared with just 19% of women living in low-income countries. 25% of men from low-income countries have access. (Source - T. Khokhar and H. Maeda. 2016. “Four Charts on gender gaps we still need to close”, op. cit.)

I think this is where microfinancing steps in and Nobel prizes are won. The idea of keeping the loan amount small but useful and doing away with the concept of collateral has transformed and assisted the lives of billions of people at the lower end of the pyramid. The organizations which had the courage of administering something of this kind can still be counted on fingers, however, their impact has been huge and has also helped in shaping government policies when it comes to lending money to the poor. I would call this a monumental, tectonic shift combining micro and behavioral economics in a beautifully woven organic and sustainable fabric.

Till now I have been able to read about two such organizations and I will be focusing on the way women have both propelled and benefited out of these structures. The first is Muhammad Yunus’s Grameen bank in Bangladesh and the second Ela Bhatt’s SEWA, which is short for Self Employed Women’s Association based out of Ahmedabad. Both of these organizations have been exemplary in fostering highly effective and inclusive microfinancing frameworks.

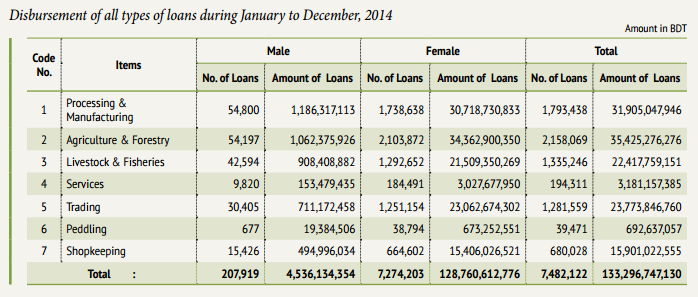

For Grameen Bank, I will use the table below to speak out for itself -

(Source - http://www.grameencommunications.net/grameen_bank/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/GB-2014.pdf)

I cannot emphasize less on the two numbers which show No. of loans taken by men and women. Of the total number of loans taken female share is 97.2% of the total. This translates into a ridiculous 96.5 percent of the overall loan amount. Not to miss out on the point that the recovery rate on Grameen Bank loans is outstanding—almost 98 percent, which is way higher than the conventional banking system which feeds on the top end of the pyramid.

Muhammad Yunus, as a matter of fact, was advised to change the name of Grameen Bank to Grameen Women’s Bank, an idea which he, of course, didn’t buy into.

As in the case of SEWA, I got to know about this organization in particular last year while we were hunting speakers for our university TEDx conference. Ela Bhatt’s (founder of SEWA) name was suggested. When I read about her, I put forward a resolute disclaimer for even trying to get her on our speakers’ roll. The reason was simple, our stage was too small to host a personality like her. The quantum of lives that she could impact with her Gandhian methodology has been a momentous social entrepreneurship feat.

Apart from the economics side of things, SEWA’s major focus was towards formulating strategies for women to confront systematic discrimination or deprivation in the workplace, community or society. Offering new alternatives and promoting small-scale entrepreneurial setups have succeeded in organizing women to enter into the mainstream of economics and markets. Although SEWA has evolved further and expanded its objectives to the Eleven-questions-of-SEWAapproach, the core idea was and is driven forward by giving self-employed women engaged primarily in the unorganized sector a greater control of money.

SEWA as per a 2013 report, had around 19 lakh members (all women). Their lending scheme runs across vegetable selling, chikan embroidery work, bidi manufacturing, sewing, domestic service and many more.

Although the SEWA model hasn’t been scaled to a level it could have been, it has time and time again proven its efficacy and has demonstrated how the flow of money in the hands of women and poor can lead to confidence-building and upliftment of these groups. SHGs and trade unions have been at the core of SEWA’s operational workings.

For what matters far beyond questions of fairness, research suggests that women invest much more of the money they earn into their families than men do, meaning that female economic empowerment can have a positive ripple effect far beyond the individual. When Bunker Roy at the Barefoot College emphasizes on the idea of training women, the inference is quite direct and invariable. Further, economic empowerment is the first step towards an overall emancipation of any section/group of the society.

When the numbers of microfinanicng are taken into account, it is not just about a seasonal surge towards a higher number of women. It is an established symbiotic relation where almost opposite to the conventional banks where 99% of the borrowers are men, the microfinancing system takes women with a similar percentage under its wings.

So, what my Dadi displayed by giving significance to small-scale savings and what people like Muhammad Yunus and Ela Bhatt have done at such grand scales are explicitly-vivid demonstrations of thinking a step beyond and involving people into handling money and taking decisions around it.

[This article is a part of the process in which I have been trying to tie-up microfinancing with ICT. As for now, I have only been able to fetch some data and the demographics associated with it. For some reason, RStudio is not showing any compatibility with my elementary OS system. It would require some troubleshooting. Additionally, I have come across this book called ‘The Blue Sweater’ by Jaqueline Novogratz, the founder of the Acumen Fund. This book carries inspiring stories of people who are doing some humble and meaningful work (Acumen Fund, by the way, is one of the organisations I am looking forward to work with in future.)]