The Bhilwara Story (so far) and Musings on State Capacity

I have grown up in Bhilwara and lived there for the first 18 years and intermittently after that. The ways in which the state functions at the district and local levels has always intrigued me. Sitting here in Delhi, I have been sifting through newspapers based out of the city. It has been interesting to observe how the corona virus pandemic is being viewed and how the developments around it are taking shape.

For the initial few days Bhilwara was standing at the precipice of a massive spread of the virus. A private hospital became the hotbed for the spread. Doctors and the nursing staff of this hospital contracted the virus and without the knowledge/acknowledgement of the virus being inside them the hospital continued its work for over 10 days. Around 7000 people who visited this hospital in the previous weeks and then the many others who they might have come in contact with were all under very plausible risk of catching the virus.

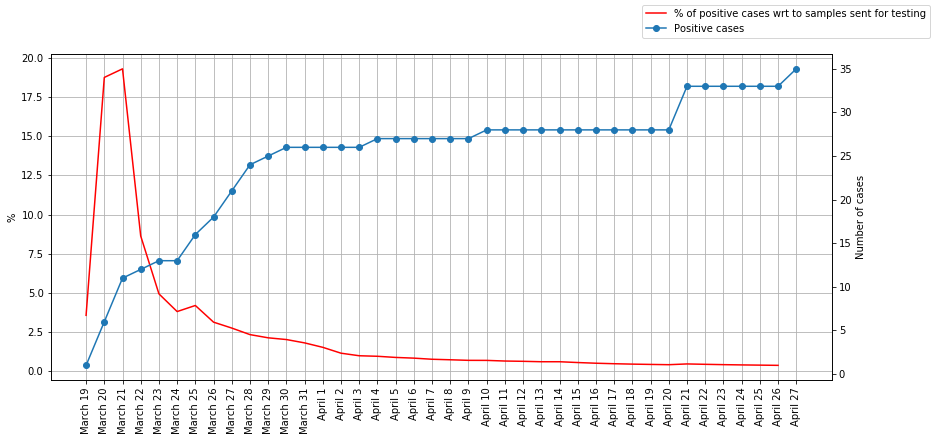

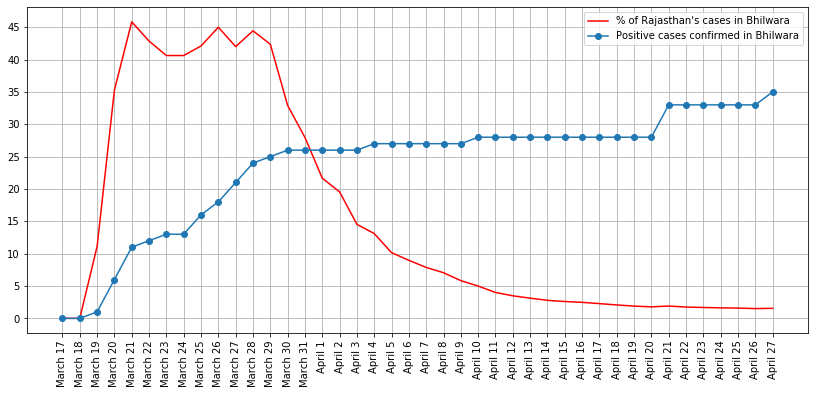

Bhilwara seemed destined to go the Italy way. The initial tests hinted towards a grim picture. Of the first 60 or so tests done, 11 came out as positive (~19%) (Fig 3). India thus far was banking on averting community spread as its way of coping against the corona virus, and here one city could have soared the numbers beyond repair. Of the first 27 cases, there were three doctors and 14 nursing staff from the same hospital, and the rest their patients and attendants.

Once the situation came to light, what followed were panic, immense luck, and some swift administrative action.

Panic because it clearly seemed the city had lost time. Luck because in retrospect, the time lost didn’t come anything close to the damage it could have caused.

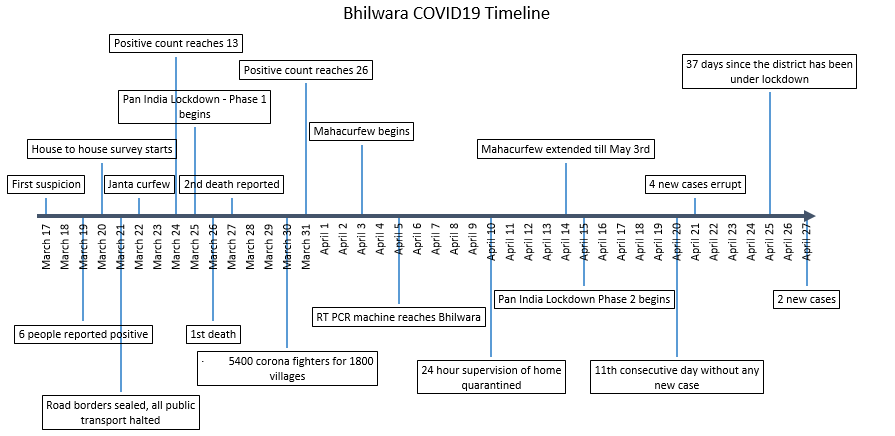

Bhilwara had put some minimal preliminary precautions in place. On 17th March when a person who had returned from Spain was suspected of carrying Covid like symptoms (reported negative on testing), he was isolated in the central government hospital. Additionally, the hospital put restrictions on children and people above 60 from visiting patients, many meetings and seminars were postponed, and a control chamber was created under the district collectorate premises. On 17th itself, the Rajasthan government passed orders prohibiting gatherings of more than 50 people.

When the first case sprung up on 19th and the scale of threat through the private hospital was understood, police curfew till 31st March was enforced throughout the district. Concurrently, the medical and health department created 300 teams to start house to house surveys to identify people suffering from influenza-like-illness (ILI). By 21st, road borders were sealed and all public transport were halted.

As described by R Bhatt, the DM of the district, the Bhilwara strategy (later lauded as the Bhilwara Model) contained the following steps – i) isolating the district ii) continuous screening to identify people suffering from influenza-like-illness (ILI) in order to identify target groups for testing, iii) testing and isolating close contacts of positive patients and putting distant contacts (as identified through the contact tracing dossier) in quarantine iv) cluster mapping v) creating 1 km radius containment areas around the identification spot along with a 3-5 km radius buffer area.

To implement the points mentioned above, the capacity of isolation and observation wards was increased, many other public utility spaces like community centres were converted into wards, hotels and guest houses were accessioned for quarantining people, telemedicine facility was ramped up, 2 war rooms were created and 325 doctors (exclusive of nursing staff) are working round the clock. Just a couple of days back Bhilwara also started testing (so far the samples were being sent to Jaipur) in the medical hospital and the daily number of tests taking place within the city are expected to rise. Further, three-tier security for healthcare officials, barricades outside the premises, a check at the entrance gate and deployment of cops at the isolation wards differentiated dedicated COVID-19 treatment infrastructure of the district.

On the other side the effort was directed towards managing and sustain the lockdown. This also includes the surveys being done to make better use of the time that has been borrowed. For the rural areas 5400 “corona fighters” for around 1800 villages were put to action. They included 5250 ASHA workers and other volunteers. Police, home guards, and social workers together ensured food and supplies reached homes within the containment area. Total shutdown meant people got essential goods including dairy, medicines, at their doorstep at call. At least 4-5 control rooms of several departments became operational.

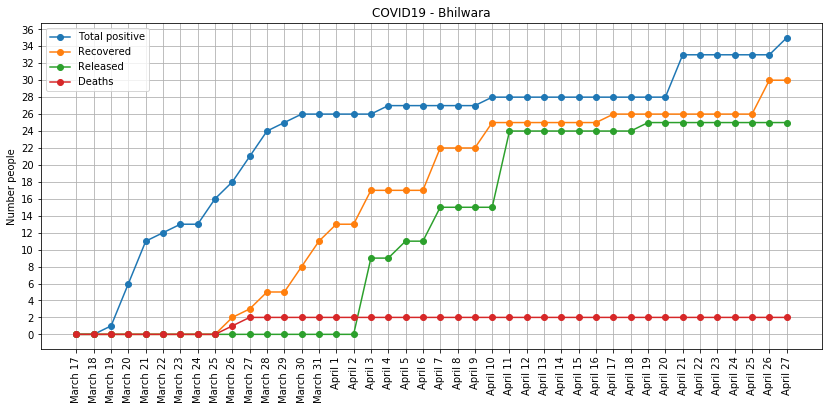

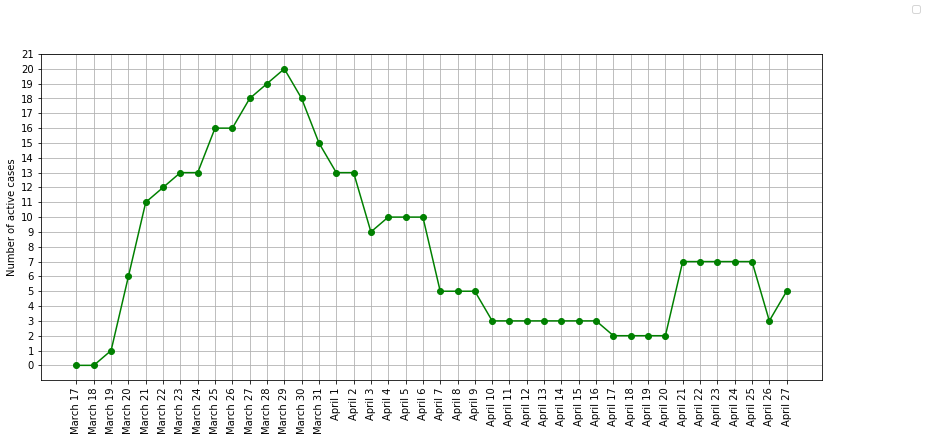

Looking at the present number of positive cases (Fig 3), it wouldn’t be wrong to call the Bhilwara strategy of ruthless containment a success. Where the potential cases could have been in thousands, the present active cases (Fig 4) are in single digits. From being the worst hit district in Rajasthan (having the highest number of cases in Rajasthan from March 20th to April 2nd) to not reporting new cases for 11 straight days, the efforts have led to impressive results.

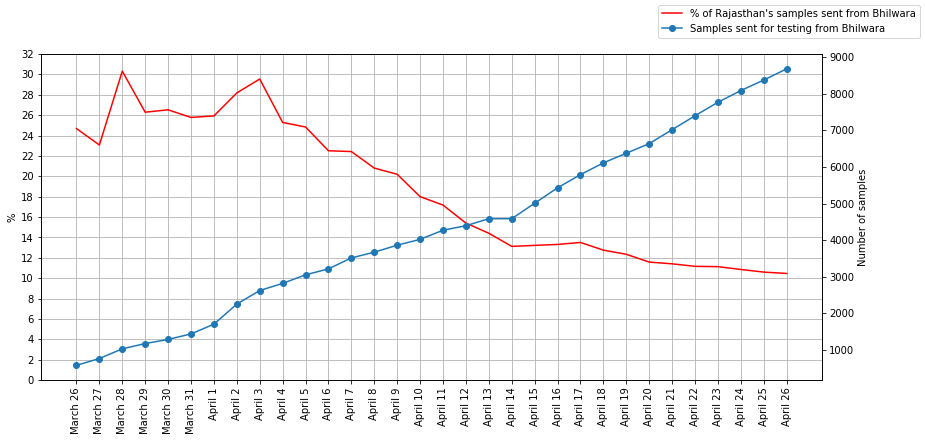

Bhilwara is still in the list of the red zone districts issued by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Though the number of cases compared to the total in Rajasthan has gone down below 2% (Fig 5), the number of samples tested from the district comprise of more than 10% of the state (Fig 6). The district is presently under “mahacurfew” (intense curfew), and with new cases erupting in the past few days, it doesn’t seem that the guard will be put down soon.

As is with the whole of the world, the economic implications of the corona virus pandemic are going to be huge for Bhilwara too. There will be various projections of the scale at which the losses come. As the city is famously touted as a “textile” city, it gives a chance to quantify something around the economic impact of the paralysis. Let’s look at some statistics around Bhilwara’s textile industry. The district comprises of around 450 big-small cloth manufacturing factories, spinning units, and process houses. Nearly 26 lakh meters of cloth is produced daily. There are 27 textile markets and around 2000 textile related shops. The yarn and cloth are exported to over 70 countries. With an average one-day turnover of rupees 41 crore, the loss in revenue so far just in the textile sector alone stands at around 1400 crore rupees (from March 20 to April 25). The most significant number though is the roughly 1.25 lakh people that are employed in textiles.

The livelihood of many of these people along with others from different sectors will now look to the state for survival and sustenance. The state’s first responsibility is the marginalised. They are also the most crucial part of the economy. They lubricate its wheels and generate demand. Does the state carry first the intention and then the wherewithal to cover up for the disruptions due to loss of income will be crucial in deciding the “new normal(s)” we will step into.

The experience of Bhilwara in dealing with the corona virus challenge gives a contextual case to think about the nature, scale, and efficacy of the state and its machinery on the ground.

So far the lockdown has been managed in an interesting way. As one of the early boomers, the district had few other places to look at (except a few in Kerala) for containment strategies. The shutters were pulled down along with rigorous door to door surveys. It would be difficult to say a word about the sincerity of effort in keeping stomachs full without hearing all sides of the story, but based on the available observations, it does seem that essentials were provisioned and the blindspots were discovered and filled up quickly. Overall, in comparison to other parts of the country, the cases of police brutality have been less heard of as well.

In policy and by extension in governance the terms hammer and scalpel are frequently floated around. The scalpel approach requires time and diligent attention to detail. The present crisis does not afford that to the governments. The pragmatic ones have gone with the hammer. To hammer early and thoroughly was the key to most of the successful instances of containment. But not everyone can hammer down like a China does. Indian state has rarely been successful (though quite reliant on it) with it. But in this case, India too had no other option and it went ahead with the approach of a complete lockdown and an almost shutdown. The bigger questions which will be answered by time are – can/did the Indian state hammer well in this instance? Can/did it hammer without leakages? Can/did it minimise the negative fallouts which come with the hammer approach? Will the hammer be more lethal than the virus itself?

The consequences of shrunken activity are and will be felt differently by different sections. Today, those who bear the maximum brunt due to both the pandemic and the resultant measures are the farmer and farm labour, the migrant worker, the unemployed, those in the unorganised sector, the rural poor, and the small entrepreneur. They are paying the highest price for the necessary but unbearable lockdown. I strongly believe that it is not what the state does now that is going to make much difference. Yes, saving lives is an imperative of the present but both present and future consequences are based in history. What ministers and administrators will do now will not be able to absolve them of the detrimental impacts due to prevalent inequalities, poor health infrastructure, grossly inadequate health budgets, boastful corruption, etc. This pandemic and the measures taken will infact amplify the socio-economic ills and create bigger groundswells around societal fracture points. Location tracking apps with similar features will be received differently based on the particular government’s past record of transparency and accountability with handling data of its citizens.

The scale of state and administrative operations at the district level has always baffled me. In normal times, the state though widespread and ubiquitous mostly shares a bad-faith relationship/arrangement with people and society. Situations like the present have turned out to be game changers in the way people perceive the state (especially at the district administration level). For districts which have shown even some glimmers of a sincerity of purpose (like Bhilwara has), the perception of people towards the state has transformed from that of intentional dishonesty to a responsible co-party to the social contract acting as a troubleshooter/saviour/guiding light.

Administrators are at the centre of the containment processes. For local authorities are at the coalface; delivering the state to the citizens. The most challenging task remains that of leadership and keeping police, service providers and other personnel motivated for intensive work requirements which are so long-stretched and highly risk-bearing. The fact that 5250 ASHA workers who are engaged in the house-to-house surveys (which forms the bedrock of what we know as the Bhilwara model) have pending remunerations for 3 months does not bode well for where we stand and tells us why the government and societal empathy require so much more than 5 PM claps and 9 PM candle lightings. As T. Sundararaman, leading public health expert, points out – “…(the) Public Sector should have redundant unused capacity. There should be some slack in it. Whenever there is an emergency or disaster, the Public Sector should be able to expand and take on the extra load.”

The Bhilwara story is far from over. The lockdown is relatively easy to administer. It works through a command and control operation. The partial (and then full) opening up would require way more innovative planning and flexible execution. The district administration will be even more pivotal in doing so. It will be delightful if Bhilwara keeps the “model” status intact in managing what comes next.

Data: http://www.rajswasthya.nic.in/

Newspapers referred: Daily Lokjeewan and Rajasthan Patrika